This year, the prestigious “Golden Minbar” International Film Festival took place in Kazan from September 6 to 11. Celebrated for two decades in the capital of the Republic of Tatarstan, the festival embraces a profound motto encapsulated in its slogan: “from intercultural dialogue to the culture of dialogue.”

Ancient Kazan offers a favorable opportunity to truly grasp the essence of dialogue culture. Each two- or three-story architectural edifice, from doors and borders to the framed windows adorned with elaborate patterns, contributes to the rich tapestry of this historical center. The winding paths that connect the main thoroughfares, along with the large and small monuments that intermittently punctuate the streets, narrate the stories of centuries and reflect the lives of numerous generations. Indeed, these historical structures impart a sense of grandeur to the city that far surpasses that of contemporary buildings and scattered modern skyscrapers, for such edifices reach not toward the sky but toward the history.

If a city does not own ancient legends, then history itself does not exist there, or it has been forgotten. There are many historical legends in Kazan. For example, according to the claim when Ivan Grozny occupied the city, he proposed marriage to the khan’s widow. In response, the Khan’s wife made a condition to the tsar – to build a seven-story palace in a week. He accepted the condition and built a seven-story castle in just seven days. As soon as the palace was completed, the khan’s wife made suicide from the top of the exact place. The city’s inhabitants named after the castle: Suyunbika

In reality, the construction of the castle took over two years. In 1552, after capturing the city of Grozny, Ivan brought Suyunbika to Moscow, where he arranged her marriage to one of the princes. Consequently, Kazan emerged as one of Russia’s most formidable strongholds towards East. One interesting historical fact is that after the capture of Kazan, the local Turkic population, referred to by the Russians as “Tatars,” relocated to the opposite bank of the Volga River. There, they established a settlement known as the Tatar village, remaining separated from their native city for centuries. According to one legend, during the winter holidays, the Russians living in the city and the Tatars from the countryside would compete on the frozen Volga River, transforming their anger into a contest of strength and resilience.

We festival participants humorously dubbed this aforementioned interesting narrative the “Dialogue of Cultures.” This jest held a kernel of truth.

This year International Kazan Film Festival commemorates the 20th anniversary. In celebration of this momentous occasion, a remarkable total of five hundred films from forty-seven countries, encompassing a diverse kind of formats and genres, were submitted for consideration. The selection committee undertook the task of curating fifty-one films for inclusion in the main competition. The challenge of distilling fifty-one exceptional works from an initial pool of five hundred is undoubtedly arduous; however, the true test of the jury’s discernment lay in their obligation to designate a singular film as worthy of the Grand Prix. The deliberations among the juries, coming from ten distinct nations—including Turkey, India, Iraq, Oman, Egypt, Uzbekistan, Russia, Kyrgyzstan, and Tatarstan—were marked by a palpable intensity, often bordering on heated debate. Such discussions mirrored the festive competitions I mentioned above as a reminiscent of the dialogue of cultures, that take place on the frozen Volga River in winter. Yet, unlike those physical contests, this particular competition was waged through the power of rhetoric, persuasion, and intellectual reasoning. Given the exuberant character of the jury chairman, Metin Gunay—a prominent Turkish director celebrated for the acclaimed “Ertogrul” TV series and a luminary in Kazan—it is not difficult to envision the elevated level of discourse and engagement that characterized these deliberations.

I was the jury chairman of the NETPAC category. One of the films included in the full-length fiction nomination of the main competition should have been awarded a special prize of NETPAC by our group. Therefore, in this report, I will talk only about the ten films included in this nomination.

The title of the film “Baurina Salu,” directed and written by Kazakh filmmaker Ashat Kuchincherekov, remains untranslated in any language. This term refers to an ancient custom in Kazakhstan wherein, upon the birth of a child, parents entrust their offspring to the care of their grandmother for upbringing and education. As the child matures under the grandmother’s influence and eventually returns to the parental home upon reaching puberty, she/he often encounters a sense of alienation, feeling as though he is surrounded by strangers in an unfamiliar environment. This estrangement manifests as an almost insurmountable barrier between father and son. If there was a nomination for “Best Child Role” in the competition, the teenager who portrayed the lead character in this film would undoubtedly be the first candidate. Overall, Kazakh cinema is frequently lauded for naturalistic performances of actors.

In this setting, everyone has a role: one person is in the kitchen preparing a daily meal for remote villages, another is carrying ice to preserve food from spoiling in the heat, while others are tending to the fields or digging graves. The actor portraying the father is engaged in taming a newly brought wild horse for the farm. The cast members immersed in these household tasks often seem to forget they are being filmed, resulting in a remarkable reportage effect throughout many scenes. This authentic style effectively persuades the audience.

However, while the director demonstrates considerable skill in keeping the actors engaged, he struggles to manage the dramatic material. This is understandable, as the depiction of the malice of ancient folk customs becomes exaggerated and cannot be brought to an end.

The film “Evolution,” made by Uzbek filmmakers, is divided into four segments, each corresponding to one of the fundamental elements of nature and have the same name: Water, Air, Fire, and Earth. The narrative commences with Fire, portraying a prodigious boy who, having graduated from school with a gold medal during the last years of the Soviet Union, speaks both Eastern and Western languages at the level of his native language. He voluntarily enlists to fight in Afghanistan, where he sustains injuries and is taken captured. He navigates through the flames of conflict and prepares to wed the daughter of the Mujahideen leader who rescues him; however, this plan falters. He manages to escape from the wedding ceremony, which ends in a bloody tragedy. Subsequently, he flees to a Western country, where he establishes a business from the ground up and amassing considerable wealth. Nevertheless, he becomes embroiled in a series of conspiracies, wherein each assassination attempt on his life inadvertently results in the demise of another. In a conclusion, he ultimately returns to his homeland, weathered by age and stripped of his fortune. The efficacy of a cinematic work, even with successful findings, diminishes when it is laden with conventional ideas and predictable tropes. All this becomes interesting and thought-provoking when it is born from the cinematographic material itself and discovered in the film itself.

The term “ideological orientation,” frequently employed in Soviet-era film criticism, denoted the extent to which a film aligned with the policies of the ruling party. In contemporary era, this concept has been supplanted by the French term “engagement,” which means directing a film (or other creative product). In the Algerian film “Furulo,” featured in the festival’s section for full-length feature films, this terminology is immediately evident. The narrative captures the myriad struggles faced by a nation that has emerged from the shackles of French colonialism. The film underscores how the pervasive lack of education in remote areas significantly exacerbates the hardships endured by the populace, often reaching intolerable levels. At the solemn conclusion of this film, which received financial support from the Ministry of Education and Culture of Algeria, the young protagonist, Furulo—the beacon of hope for his family residing amidst the imposing mountains—is dispatched to the city to pursue his education. In terms of its narrative structure and general mood, the film bears a certain resemblance to Satyajit Ray’s “Road Song”; however, originality and plausibility are not missing in this film. The exploration of social issues, coupled with ethnographic elements, captivates the audience and provides a sense of enjoyment.

Houshang Gulmekani is renowned as a film critic, playwright, and author in Iran. As the founder and editor-in-chief of the film magazine “Film Emruz”. This year, marking his seventieth birthday, he made his directorial debut with the film “Ahu,” an adaptation of his own novel. Like writing memoirs, diaries, books, to make a film can flourish at any stage of life. In fact, audiences are introduced to a refreshingly innovative perspective during this period of his career. Moreover, as it increasingly becomes a norm for directors to also serve as screenwriters for their own films and to write plays for theatrical productions, it stands to reason that in the near future, adaptations of works by authors will be embraced as a natural evolution of creative expression in alternative formats in films and playwrights. Why not celebrate this burgeoning trend? This should be applauded.

“Ahu” is translated as “Gazelle” in both English and Russian (Газель), a title that addresses with the term “ghazal” in our own language. Following the film’s screening, the director mentioned the genre of ghazal in Eastern literature, asserting that the film is crafted within this stylistic framework. This ninety-minute cinematic experience, while lacking a conventional plot, unfolds with moments of intrigue that consistently subvert audience expectations, revealing that their anticipations of forthcoming events are ultimately wrong. Against the backdrop of the infinite harmony that pervades the natural world, all problems immediately disappear as if they had appeared microscopically. Yet, what remains unblemished is beauty itself; One can only speak to eternity in the language of beauty. A beautiful, young lady, an artisan of wood carving art comes to a happy corner of nature consisting of forests. In this setting, all visitors are strangers, arriving only to vanish as mysteriously as they came. Ultimately, in a poignant conclusion, the young woman also disappears, leaving the audience confronted with an expansive, breathtaking, and slightly daunting vastness.

During a meeting with the director, an audience member inquired whether Tarkovsky had influenced his filmmaking. It is likely that the question referred to the iconic film “Solaris.” Gulmakani expressed his gratitude for the mention of Tarkovsky in relation to his work but acknowledged that he drew greater inspiration from Krzysztof Kieslowski and Abbas Kiarostami. Personally, I also recognized certain episodes in this film that echoed from “Solaris.” Nevertheless, this observation does not in any way diminish the film’s originality and innovative qualities.

As a person immerse him/herself in one film after another at the Kazan festival, it felt as though the eyes were taking a much-needed respite from the European and American films, which often served as mere desserts following a substantial, hearty meal. Europe and America have certainly made their mark on cinema, but now they seem preoccupied with crafting visually pleasing, deceiving confections. In contrast, as if, films originating from Asia, particularly in Islamic countries, offer a sense of exploration into uncharted territories, where hidden depths remain undiscovered and new narratives are continually sought.

The NETPAC jury found themselves divided in their decision for the Best Film award, particularly torn between two noteworthy entries. One of these films, “Joseph’s Son,” was made by the young Indian director Haobam Rahab Kumar, based on his own script. The narrative revolves around a young football player named David, who has been missing for three days. Concerned, his mother dispatches his father to search for him, prompting the father to contact the police. They inform him that a young man’s body has been discovered in the morgue several settlements away. Undeterred by the recent escalation of ethnic tensions in the mountains, which have resulted in daily murders, the father commences on a journey to the exact place. As he confronts death repeatedly, ultimately arriving at the morgue, where he is faced with the grim task of identifying the corpse. Whether it is indeed his son remains a mystery, as the filmmakers deliberately conceal this revelation from the audience. We want to read it from the face of the father. Remarkably, this actor, manages to professionally maintain the suspense. Following the screening, in a personal conversation with the director, it was revealed that upon discovering the father’s role was played by an amateur, the jury had little more to say than “bravo!” to the actor’s impressive portrayal.

The predominant motif in majority of the films presented is the concept of the road, a theme unsurprisingly as life itself can be likened to a journey. The pivotal question lies in determining the destination of that journey. In the Tatar film “Mountain of Lovers,” the narrative follows a middle-aged man, a figure of professional success, who embarks on a quest to find his estranged father, a man he has never met, in a distant city. The backstory reveals that his mother, who was once deeply in love, never remarried after her beloved was conscripted and sent to war. Now an elderly woman who never married, remains in her dilapidated home, which is scheduled for demolition, perpetually awaiting the return of the man she loved. As the son locates his dying father in the other city and bring him back in his car. Throughout the drive, we observe the complex, tense but extremely intimate father and son relationship. Director Salavat Yuzeyev made this film as an adaptation of a play written by his father, Eldar Yuzeyev, a renowned playwright of Tatarstan. In creating the film, the director seems to have summoned the spirit of his late father, embarking on a journey with him that culminated in the production of an extraordinarily personal cinematic work. What is particularly interesting is that this film resonates deeply with every Tatar audience member, becoming a personal narrative for all who watch it. This was evident in the enthusiastic reception during after screening discussions, where the film was met with fervent acclaim. I must admit, I felt a pang of jealousy witnessing such an overwhelming response. The film is narrated on a folk song. This raises the question: do not we possess a theme like this that had the potential to become a cult classic for generations of Tatar viewers? I urge fellow directors to refrain from pursuing superficial trends or imitating European cinema; instead, let us embrace our rich cultural heritage—our folk songs, mothers’ prayers, the responsibilities of sons, and the devotion of elderly fathers—as the foundation for our cinematic endeavors. Let please local audience greatly. Create films for audience.

A significant battle erupted over Sri Lankan director Prasanna Vizenej’s film “Paradise,” with jury member and especially esteemed screenwriter Yusup Razikov emerging as a fervent advocate for the film, even demanding for the Grand Prix. The exploration of social issues follows two young individuals—a young man and a woman—who seek relaxation in a region of their country renowned for its paradisiacal beauty. However, during the midnight, their laptops, integral to the boy’s future and business via his connections with the ruling elite, have been stolen. So, he demands the local police to locate and return his laptop within a day, threatening severe repercussions if they fail. Alarmed by this ultimatum, the police resort to harassing the already hard-set local population. The situation escalates tragically when an innocent boy becomes a victim of brutal torture and ultimately dies, igniting public outrage. Ironically, the boy who originally demanded the return of his laptop also dies to the ensuing chaos. Before our eyes, a once idyllic paradise transforms into a veritable hell, revealing the unsettling truth that it is humanity that constructs such hellish landscapes; without people, the world would undoubtedly remain a paradise.

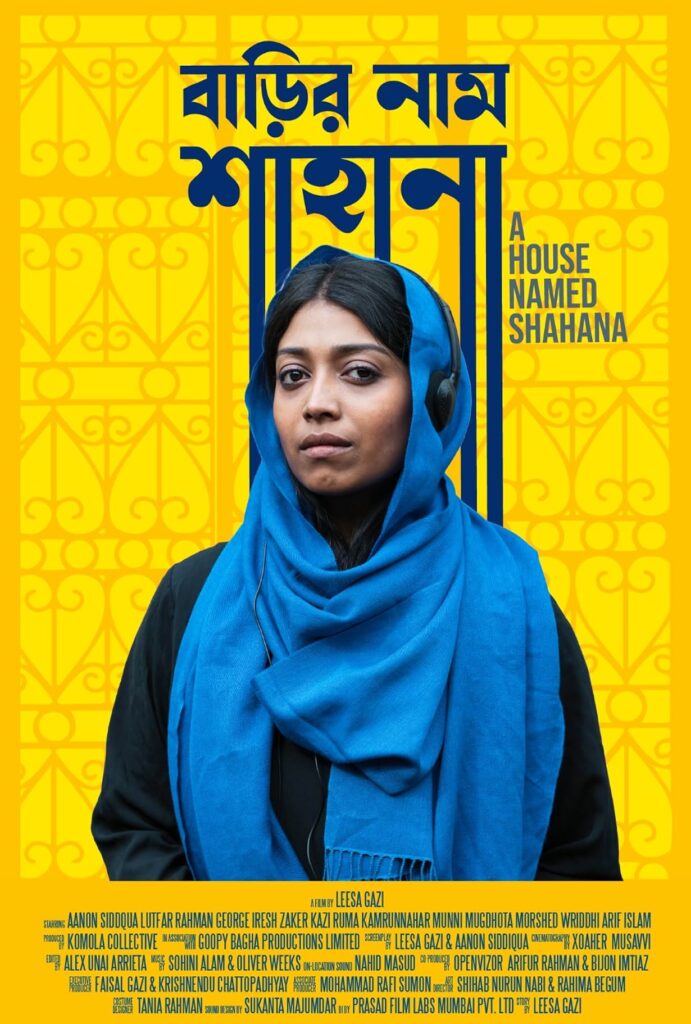

Similarly, the film “The House in the Name of Shahana,” directed by Bangladeshi filmmaker Lisa Ghazi, raises pressing social issues through the narrative of a young girl named Dipa. At just seventeen, Dipa elopes with her beloved, only to soon discover that he has a hollow and soulless existence. Disillusioned, she abandons him and returns home, the father forgives her as he grapples with his illness and loneliness. Shortly thereafter, a wealthy, devout man approaches Dipa. She finds herself shackled to a religious husband who imposes stringent conditions, leading her to divorce him within a month and returns home again. Compounding her struggles, another problem for Dipa is that the house they live in with her father is the property of her uncle, a traditionalist who is stricter than her ex-husband. She feels compelled to comply with his demands, primarily due to her father’s deteriorating health. But when we find out that this house is actually named after Deepa’s late mother Shahana, the conditions are perfect for the happy ending of the film. A woman chose death as a means to escape the oppressive local customs like a bird, she flies away from this house. In contrast, Dipa opts for life and the promise of an education in America, symbolizing a rejection of antiquated traditions in favor of Western liberal values. I liked the title for the film. Shahana remains a spectral figure, who is said to have been a magnificent woman as her name meaning suggests. There is no doubt on that. Naturally, Dipa as a daughter inherits the strength and resilience. Dipa emerges as a formidable character, capable of defying the shackles of ignorance and tradition, ultimately achieving triumph. Her journey echoes the legacies of female protagonists in our literature and cinema, like Sevil and Almaz…

Yakutian cinema has garnered significant acclaim over the past decade, triumphing at numerous festivals and securing prestigious awards. This year’s film festival in Kazan was no exception, with the jury bestowing the Grand Prix upon Alexei Romanov’s “Legends of Eternal Snow” by a decisive majority vote. The film is imbued with evocative imagery: snow, fire, yurts, fur, spirits, and a faint, ethereal hum underscored by distant, monotonous music—elements that are emblematic of Yakut cinema.

Based on the story written by Nikolay Zabolotsky in the tale genre, this film has the same elements which intertwines two poignant legends. The first follows an affluent yet elderly prince, residing far from the tale’s setting, who learns of a beautiful girl and dispatches a messenger laden with gold and gifts. The girl’s parents, eager to secure this wealth, willingly send their daughter to the aging prince, who wishes to avoid dying alone. However, the girl’s desires are never considered. The second legend centers on a stunning girl whose parents succumb to a devastating infectious disease. Despite her legendary beauty, suitors shun her. Desperate, she constructs a yurt by the roadside, where passing travelers stay and experience a night of paradise. Each down, hoping to be killed every time, the girl reveals to them that she is contagious. Hearing this, young men run away for their lives and die somewhere. The girl who cannot stand it anymore and hang herself. One of the survivors from her encounters, who shared in the heavenly journey, remains alive and later emerges as the leader of the group that leads the group who bring the girl from the first legend to the old prince. Yet, the spirit of the deceased girl seeks storm for the life of the survivor, saves the bride taken for the dying prince in the first legend.

The allure of fairy tales is loved by the audiences, leading the jury to award the Grand Prix of the festival to “Legends of Eternal Snow.”

However, the film “Glass Curtain,” awarded by NETPAC for “Best film” directed by Turkish filmmaker Fikret Reyhan, stands in stark contrast to a fairy tale, drawing more parallels with the ancient Greek tragedy “Medea.” Despite Nasrin belonging to the same social class and having a four-year-old son, she finds herself estranged from her husband, Omar, a man who feels like a complete stranger, his character fundamentally incompatible with hers. Nasrin is preparing to marry Salim, a young man she loves, and she is already pregnant with his child. Omar’s parents adamantly refuse to allow Nasrin custody of their son, while Omar himself insists that, even in death, he would rather not see his son grow up in the home of another. Salim, hailing from a different class and maintaining close ties with prosecutors and other officials, seeks to knock Omar down to size and intends to imprison him for his relentless pursuit of Nasrin. Yet, Nasrin opposes this course of action. Internally, she grapples with her future, unable to envision a life with Salim any more than she can reconcile her past with Omar. At the film’s conclusion, she calls a doctor for an abortion. Subsequently, as she walks through the streets, Omar follows her, and eventually, both of them vanish. The audience is left with an empty street, pulsating with life, yet devoid of its protagonists.

The film “Glass Curtain” can be classified as part of the genre often referred to as “serious cinema.” As we understand, cinema is captured through the lens of a camera, which is made of glass. Thus, a metaphorical glass curtain exists between our perception and the actual events depicted in the film. Consequently, the audience perceives only approximately thirty percent of the unfolding narrative, while the remaining percentage remains on the unseen side of this curtain.

Consequently, I departed from the festival with a wealth of impressions, acutely aware that perceiving even thirty percent of the experience is far superior to witnessing none at all. As we currently lack a real festival of our own, our understanding of the cinematic landscape is primarily derived from articles and the festivals we have attended. However, it is likely that we will one day have the honor of hosting one of these esteemed festivals ourselves.

Nadir Badalov